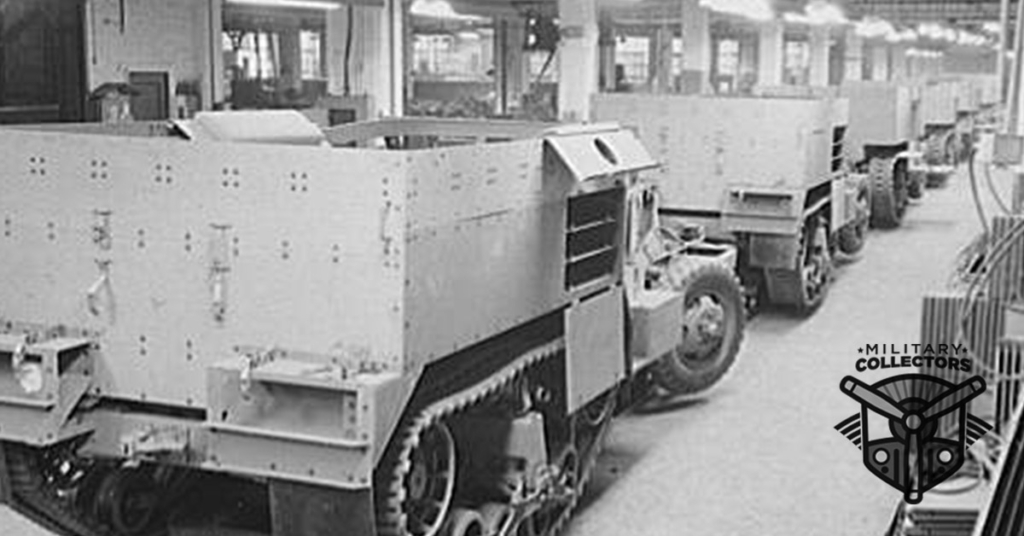

M2 Half Track Car

Few vehicles have made as much of a difference in impacting world history like the M2 Half Track Car. The M2 halftrack vehicle was originally intended to be used for hauling artillery, but it was applied to a number of other uses by the U.S. armed forces. The M2 was deployed to North Africa, the Pacific, and Europe during World War II.

The M2 Half Track Vehicle stands at 7.4 feet tall, 7.1 feet wide, and 19.5 feet long. Weighing in at 9.9 tons, most of it from the tracks and the armor, the large steel tracks are the primary emphasized feature of this tactical vehicle. The truck is powered by a White Motorcar Company 160AX engine with 147 horsepower, with a maximum speed of only 40 miles per hour and a maximum range of 199 miles before refueling is required. 17,000 of these were produced for military use.

History of the M2 Half Track Car

The M2 Half Track vehicle is the result on a lesson learned the hard way during the First World War in Europe: hauling weapons or other loads can be a nightmare when harsh weather ruins the roads. It rains often in Western Europe and the roads were often turned completely to mud, which then made the roads completely impassable.

The Army’ Cavalry units in particular suffered when their armored scout cars would become bogged down in mud. This problem prevented a lot of weapons, supplies, and manpower from getting to where they were critically needed during the war. Uncle Sam knew he needed a vehicle that could get around no matter how rough the weather or terrain. The next generation of tactical fighting vehicle would need to have metal tracks that could roll through any terrain.

The M2 is based on a type of industrial truck used by the French army during the 1930s. It was adapted from an old M3 Scout Car by the White Motor Company in 1938, but with the rear bogie assembly from a Timken truck added to the back. The original design, the T7, was far too underpowered for the heavy duty upgrades. After going back to the drawing board, the improved model was the M2 Half Track Car. In 1940 the U.S. government made purchase of a line of M2 Half Tracks and the White, Diamond-T, and Autocar motor companies began assembly line production.

The M2 vehicle in World War II

By the time the M2 Half Track Car entered into production, the Second World War was in full swing in Europe. Great Britain was in desperate need of vehicles, weapons, and war materials and the British received thousands of the M2 under the Lend-Lease Policy. The Germans invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, only a few months before the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. Once the U.S., UK, and Soviet Union officially became allies, over 800 units of the M2 and M9 halftrack vehicles were sent to the Soviet Union. Under the Monroe Doctrine, several M2s were given to Nicaragua and Argentina in 1942.

The U.S. military used the M2 in every theater of the war. The M2 was an invaluable asset for the Allies in the North Africa campaign, since the previous models of Scout Cars and Armored Personnel Carriers would never have been able to get over the wide desert with rubber tires. The Allies extensively used the M2 in Italy and Greece before eventually deploying the M2 to northwestern Europe in the Normandy invasion.

The Red Army deployed its limited number of M2 Half Tracks during the major counter-offensive against Germany. The U.S. Marine Corps also relied on the M2 during the long island hopping campaign in the Pacific. Like the North African desert, the dirt roads of the Philippines and the thick jungle in most of the Pacific Islands would have bogged traditional vehicles down in an instant.

The M2 Half Track on the battlefield

The M2 Half Track Car proved its worth on the battlefield in Europe, Africa, and the Pacific. While it was not specifically designed to be an offensive fighting vehicle, the M2 was in more than its fair share of firefights. As mentioned earlier, the maximum speed was 40 miles per hour, meaning its regular cruising speed would be between 20 and 30 miles per hour. It was by no means a fast vehicle, but it was not meant to move fast. It was meant to move forward, which was only possible because of the steel tracks.

It comes with armor plating over the doors, windows, and the entire cabin of the vehicle. The cabin is small and designed only to hold a crew of 2. It came equipped with a standard M2 Browning .50 caliber heavy machine gun and 1,000 rounds of ammunition to make the enemy think twice about fighting Uncle Sam. Even in its original form with no modifications, the M2 is a fearsome fighting vehicle.

Military Collector Ranking

- Collectability: ★★★☆☆

- Rarity: ★★★★☆

- Est Value: $45,000 – $80,000

Vehicle Specifications

- Weight: 5,917 lb (2,684 kg) (empty)

- Engine: Dodge T-245 78 hp (58 kW)

- Speed: 55 mph (89 km/h)

- Number built: 115,838

Battle Tested: M2 Variations

At nineteen feet long, with armor plates and a .50 caliber turret mounted machine gun, and rolling forward at 40 miles an hour, I would have taken a tank or a powerful rocket launcher to bring stop an M2 Half Track. Other variations made this vehicle even more powerful and effective in combat.

The M4A1 81mm Motor Mortar Carriage – The standard M2 equipped with an 81 millimeter M1 mortar. The doctrine was to fire the mortar dismounted, but the M4A1 was specially designed for the mortar to be safely fired while mounted on the back of the truck in a battlefield emergency.

The T1E1 – This variant of the M2 was fitted with a Bendix mount with two .50 caliber Browning M2 heavy machines guns, turning this vehicle into a mobile anti-aircraft gun.

While the M2 Half Track Car played a crucial role in winning the war, it was replaced by the M9 Half Track by 1945. The last M9 vehicles still in military use were donated by Argentina to Bolivia in 2009.